Activities for all students should include some higher order thinking skills; activities for high ability students should include more. Research shows that incorporating the higher order thinking improves student learning (and takes their thinking to new heights). A wise educator once told me, "Use HOTS, not MOTS."

Of course our students still need to know, understand, and be able to do. But it's important to take learning to the next level and ask them to analyze, synthesize, evaluate, and create.

Three ways to incorporate HOTS into our classroom include problem solving, critical thinking, and creative thinking. Critical thinking involves collection and processing of information; creative thinking requires generating many ideas, striving to find something unique, and adding to the original idea(s).

Fortunately, many of our standards have already built in HOTS. Here are some examples from the Common Core Reading: Literature standards for fourth grade:

- RL.4.1 - Students must know how to read and understand the text, but they must also analyze the text to infer then defend their answers.

- RL.4.2 - Students must summarize the text, but they must also analyze and synthesize to find the theme.

- RL.4.9 - Students must analyze two texts then compare and contrast.

For these standards (and all of the CCSS Reading: Literature standards), students start with basic skills (knowing how to read and understand the text) then s-t-r-e-t-c-h to higher order thinking. For RL.4.1, students must analyze the text to determine how best to defend their answers. RL.4.2 has shades of creative and critical thinking because students must generate ideas for theme then evaluate their ideas to find the best representation of the story. RL.4.9 is full of HOTS! Students are working with two texts to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize. In my mind, every time we ask a student to construct a response, they are also involved in a very high level of thinking: creating.

It's a relief to know that HOTS are already in play when I ask my students to write responses or solve problems to address common national or state standards. This way, I don't need to worry about it quite as much. But . . . I still need to differentiate for my students' varying needs.

Differentiation can take three forms: content, process, or product. Fortunately, differentiating just one of these can easily alter the lesson to address the needs of students in your classroom.

I tend to use content differentiation the most. This simply means asking students to read or learn material at a different level. To make my job a little easier, I might find or rewrite texts or math activities at several levels. That way I can teach just one lesson. It's more work up front, but it leaves me less frazzled during the school day. Or, when necessary, I use totally different content for different groups of learners in my classroom.

Process differentiation asks students to do something differently. For example, one group of students may be learning how to solve multiplication problems using the standard algorithm while another group uses (or even tries to invent) alternative methods. Students may be asked to analyze text or take notes differently, conduct experiments using a range of skills, etc.

Differentiating the product simply means there's a different outcome. One group may write a sentence; another, a paragraph; and a third, a five-paragraph essay. Some students might create posters while others create PowerPoint presentations or develop their own websites.

Differentiation can occur in so many ways. Possibilities are limited only by your (and your students') imaginations.

I'd like to show you how I differentiated my compare/contrast unit. Since it's a reading unit, I first thought of differentiating the content by writing the text at several levels. Folklore - - - fables, fairy tales, myths, etc. - - - are often familiar to children and can be conveyed simply. After much thought, I decided to use process differentiation instead.

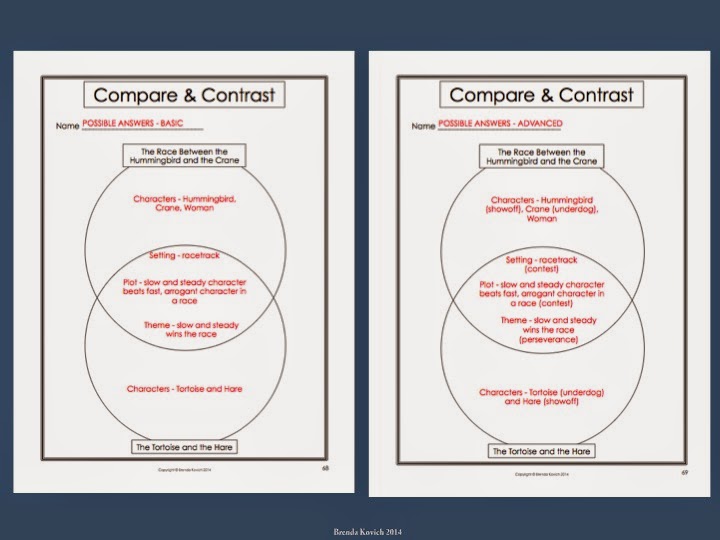

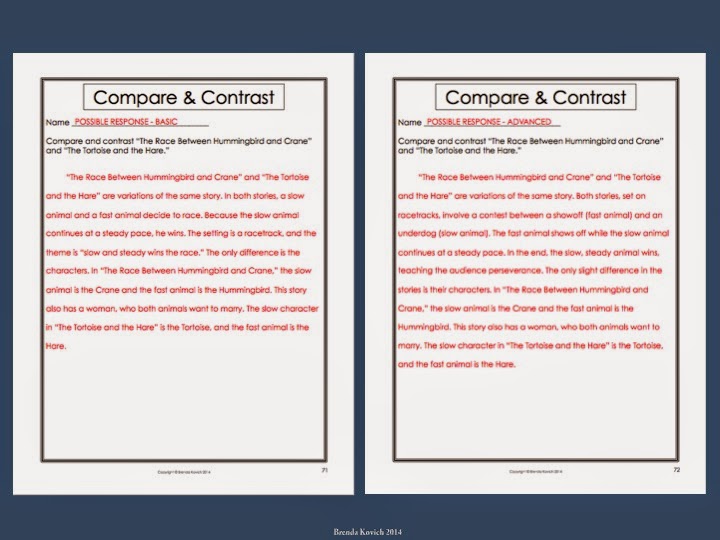

All students will use the same structures to compare and contrast two pieces of literature: first a table to analyze elements, and then a Venn diagram to compare and contrast. Students on the low end will only be required to analyze, compare, and contrast characters, setting, and plot. Average and advanced students will also consider theme. To take my advanced students to a new height, they will also evaluate each element and determine its archetype.

Here are some examples of how average and advanced students' work might differ:

Taking these next steps - - - adding higher order thinking skills and differentiating - - - takes instruction from good to great. It's easy. Just put one foot in front of the other.

Brenda

No comments:

Post a Comment